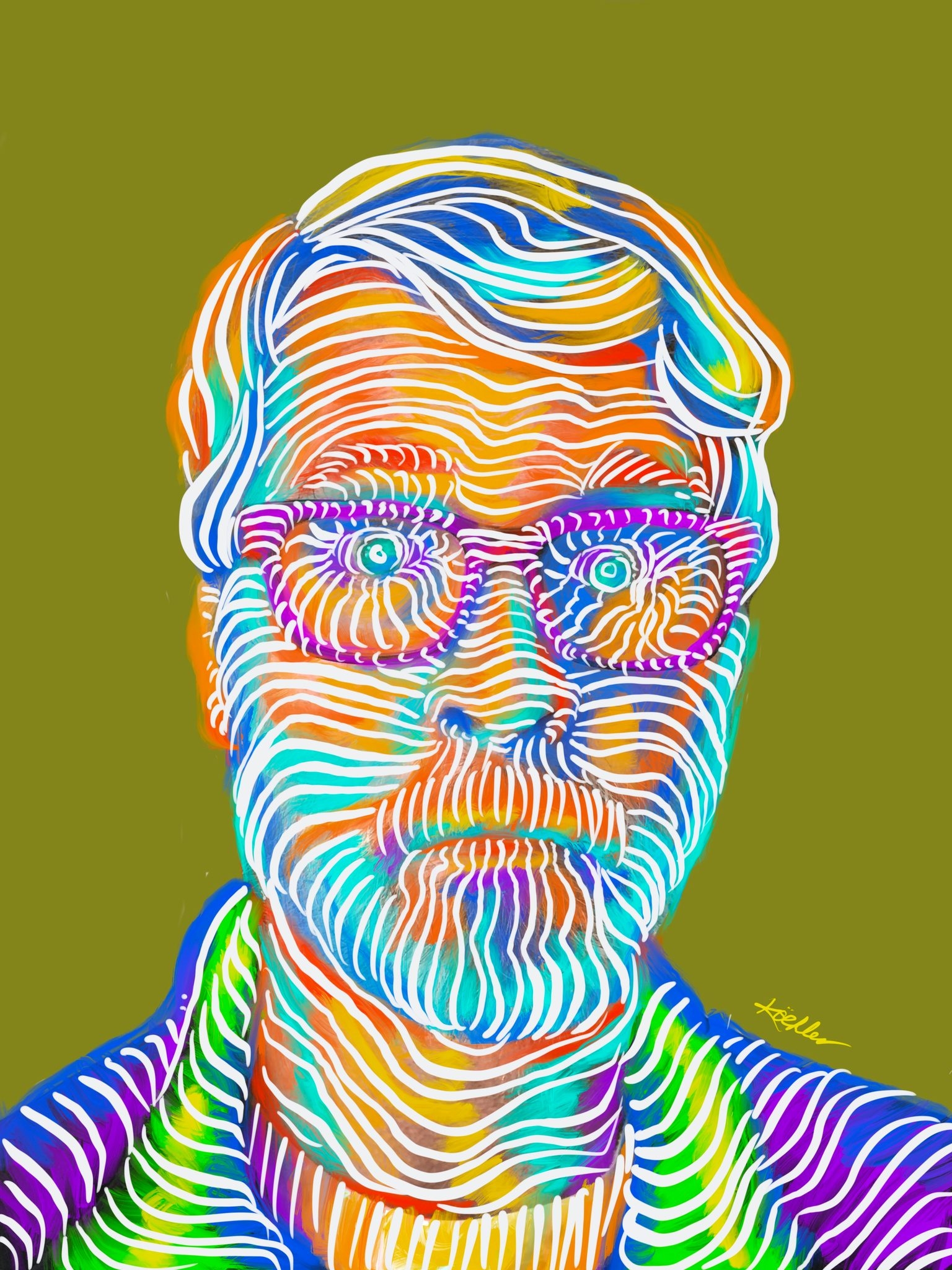

About the work

In late 2018, John Koehler acquired an Apple iPad Pro, a pressure-sensitive Apple pencil, and a program called ProCreate. Thus began an intensive four years to master his new art tools, study techniques, and create more than 200 works of art by the end of 2021. Koehler created a series of dogs, animals, nudes, and portraits. Then in early 2022 he began his most recent work of abstracted layering, color shifts and effects, using endangered animals and angels as his subjects. Most of the work shown within this website will form the basis for a show later in 2022.

About the Artist

A gifted artist since he was a child, John Koehler’s work has crossed the spectrum of pen and ink, watercolor, advertising, graphic design, photo-retouching, illustration, and digital painting. A graduate of Virginia Commonwealth’s art program in 1980, John went on to graduate studies at George Washington University. After spending twelve years at various Washington, D.C. area ad agencies working as an art director, John started his own graphic design firm, Koehler Studios, in 1994. When he sold that firm in 2010, Koehler formed Koehler Books, a publishing company. He also worked as director of Younglife Capernaum, a ministry for kids with disabilities. He is a member of the Bürpenfärtzen Brothers, and is the 1991 Boomerang World Champ. He has two daughters, Kimmi and Danielle, and lives with his wife, Patty, in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Their 40th wedding anniversary is in 2022.

Artist John Koehler, age 4, shown with his first art patron, his mother Mary Etta Koehler.

The artist in elementary school.

In the beginning

I was not born with an art brush or pencil in my hand, much less a digital pen. Of course, in 1958 digital pens had not yet been invented, yet I seemed to have some early ability to see things and put them down on paper. This natural talent did not seem strange to me. It just was.

To me it was the same as being able to throw a rock a long way and accurately, or to pop a wheely on the move, or hit a baseball a mile. It was no big deal. Talent among boys was respected and expected.

My mother noticed my artistic talent right away of course, and her interest in my own development was a bedrock element in my growth over the years. Knowing that someone not only loved me but loved the art I created was wonderful.

My elementary school teachers noticed my talent and put me to work creating bulletin boards, an early form of advertising, which eventually I got into later in life. I thought it was fun, and it got me out of some class work. For the most part, I was a good student, As and Bs, if a bit lazy.

I never took elective art classes until my senior year of high school. I was in Art 1, stuck with low-talent, lunk-headed freshmen. Mrs. Woodhouse (may she ever be blessed) had us draw shapes and shade them. Duh, so easy, anybody could do it, right? Apparently not, and after two projects she had seen enough, and moved me back behind the screens with the Art 4 and 5 students. True artists. “You’re going to work on projects back here,” she said.

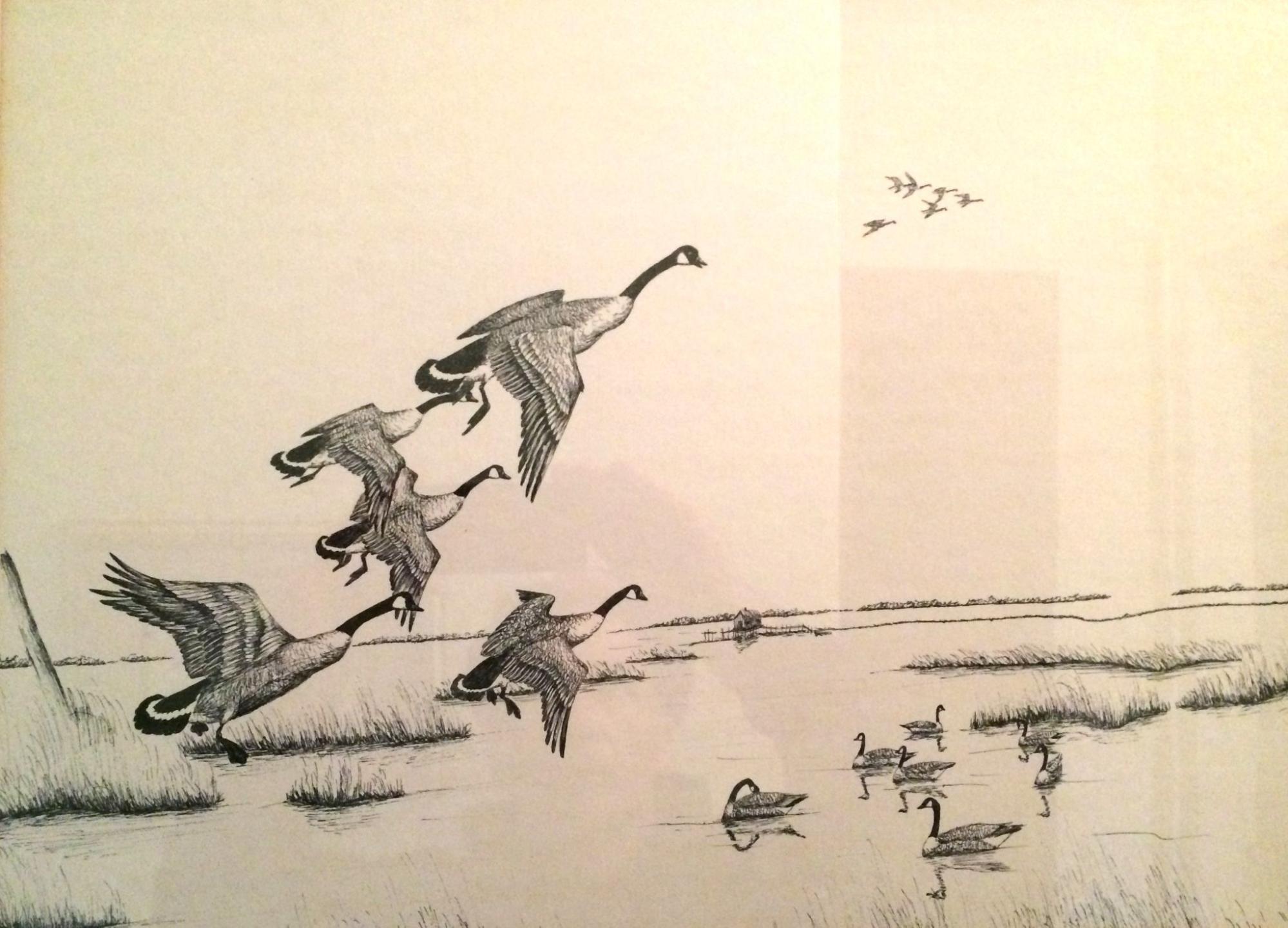

Freedom. I was into hunting ducks back then, and my hero was Herb Jones, a painter of great talent who did watercolors of ducks and scenes that were reminiscent of where I lived, and the Tidewater area in general. So I started doing watercolors and pen and ink drawings of ducks and geese. When I was done, I carried them down to the office and sold them to teachers and others in the office. As a senior I ruled the hallways.

This of course bloated my artistic ego to the point that I thought I was hot stuff. I almost got a scholarship to VCU’s art program, but my dad made too much money. Soon upon arrival I realized that my art was not all that special, as there was a tremendous amount of talent out in the art world.

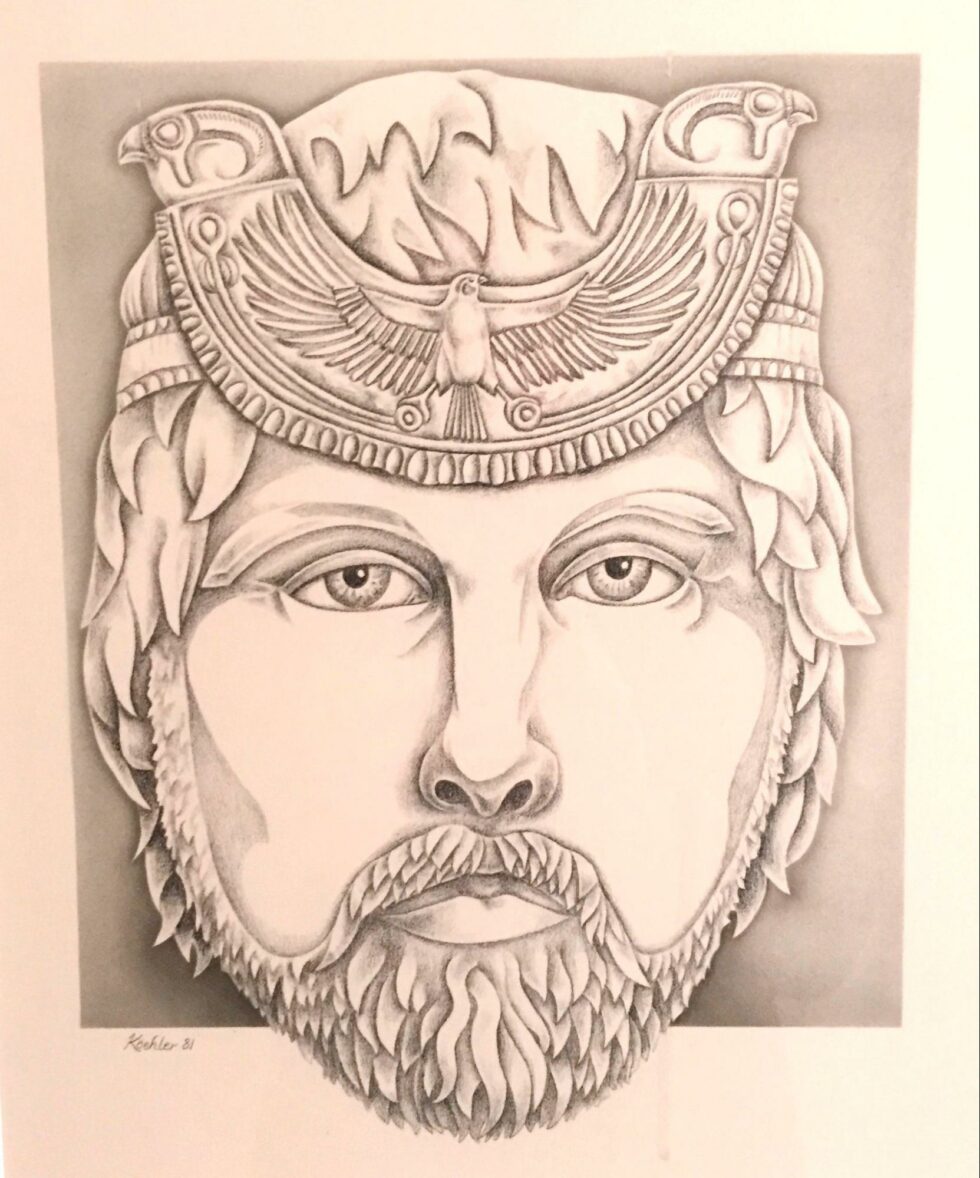

Pen and inks from high school, 1976.

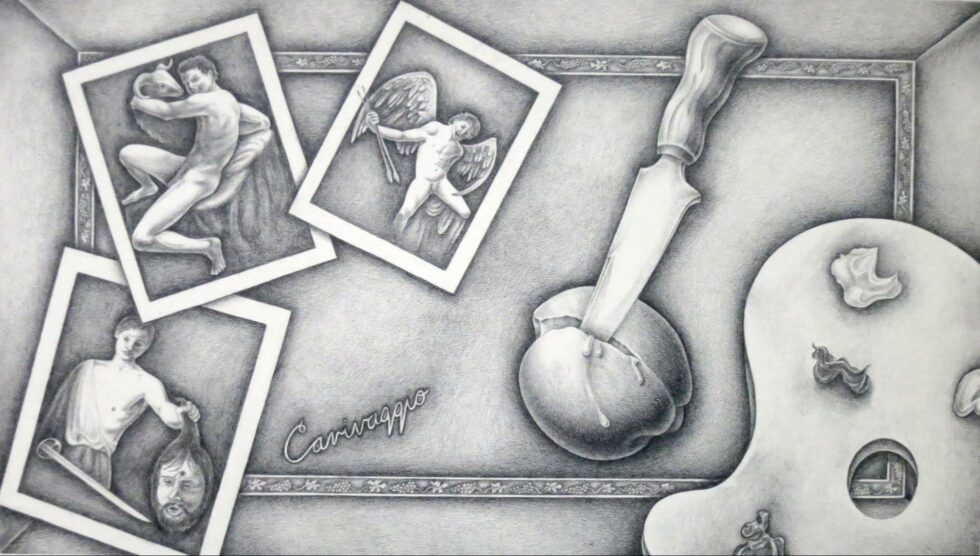

I worked hard to become a gifted illustrator. I was good and sometimes gifted but ultimately realized I probably could not make a living at it. So, I went into Communications Arts & Design, with the idea of becoming a graphic designer, where there were many more job opportunities than in fine arts and illustration.

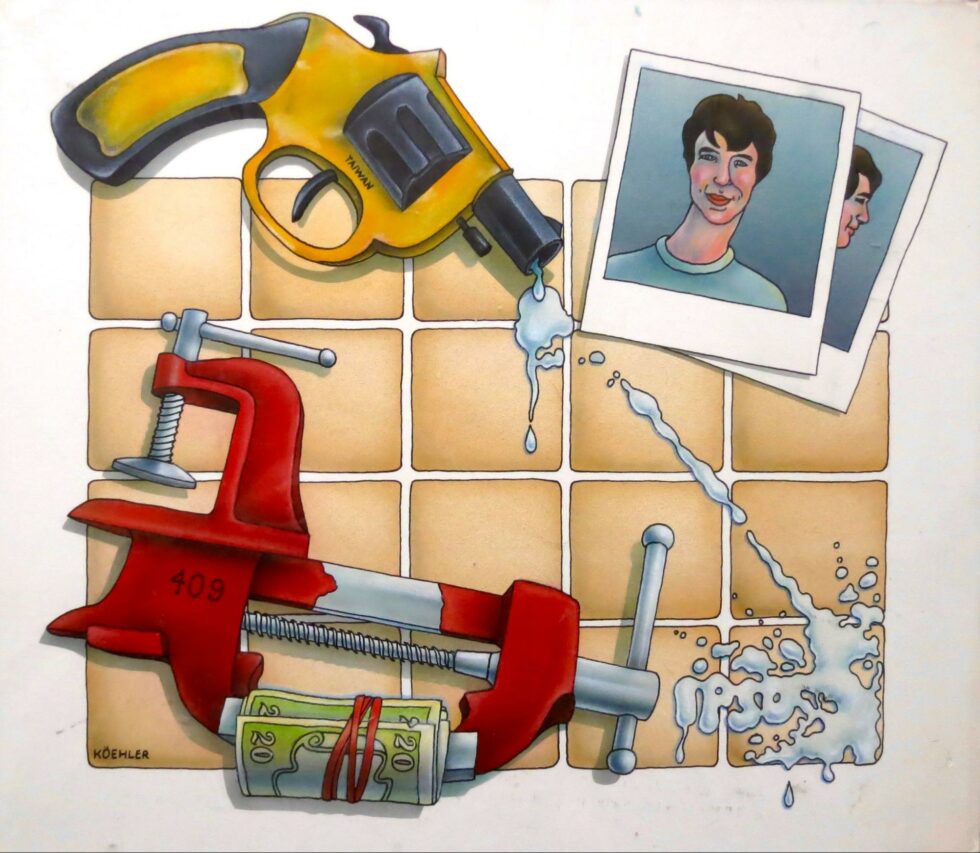

After working in the advertising world for twelve years as an art director, I decided the time was right to start my own studio. So I jumped on that crazy train and we moved to Virginia Beach in 1994. That was the time that Apple released the Quicktake 100, the first digital camera. My favorite thing back then was to take pictures of friends and clients and then use Photoshop to place them in another background, or turn them into a whale or anything at all.

I became Photoshop King in the area, and made a lot of money retouching and doing digital illustrations, using Photoshop and a Wacom tablet with a pressure-sensitive pen. The pressure sensitivity was a major breakthrough, allowing for huge advances in the art world.

Fast forward to 2010 when the first iPad was released. I made art using a program called Brushes with my finger. Who knew that finger painting would come back in style! The big breakthrough for me was that I was working directly on the art surface like paper or canvas, but in a digital world. This made the creative process more intimate, and my canvas became mobile. I read books on my iPad and also created works of art.

Three works done with Brushes finger painting app in 2011.

Fast forward again to 2018, when Apple released the iPad Pro with much higher resolution and responsiveness, along with the Apple Pencil. The Pencil is so much better than a Wacom tablet because it’s directly in touch with the art surface (the glass face of the iPad), and the responsiveness is incredible. Plus, the huge range of brush tips, from calligraphic, airbrushing, drawing, crayon, oil painting, watercolor, textures, just about any kind of brush tip you can think of. Easy to experiment and change directions on the fly, not to mention undo and alter.

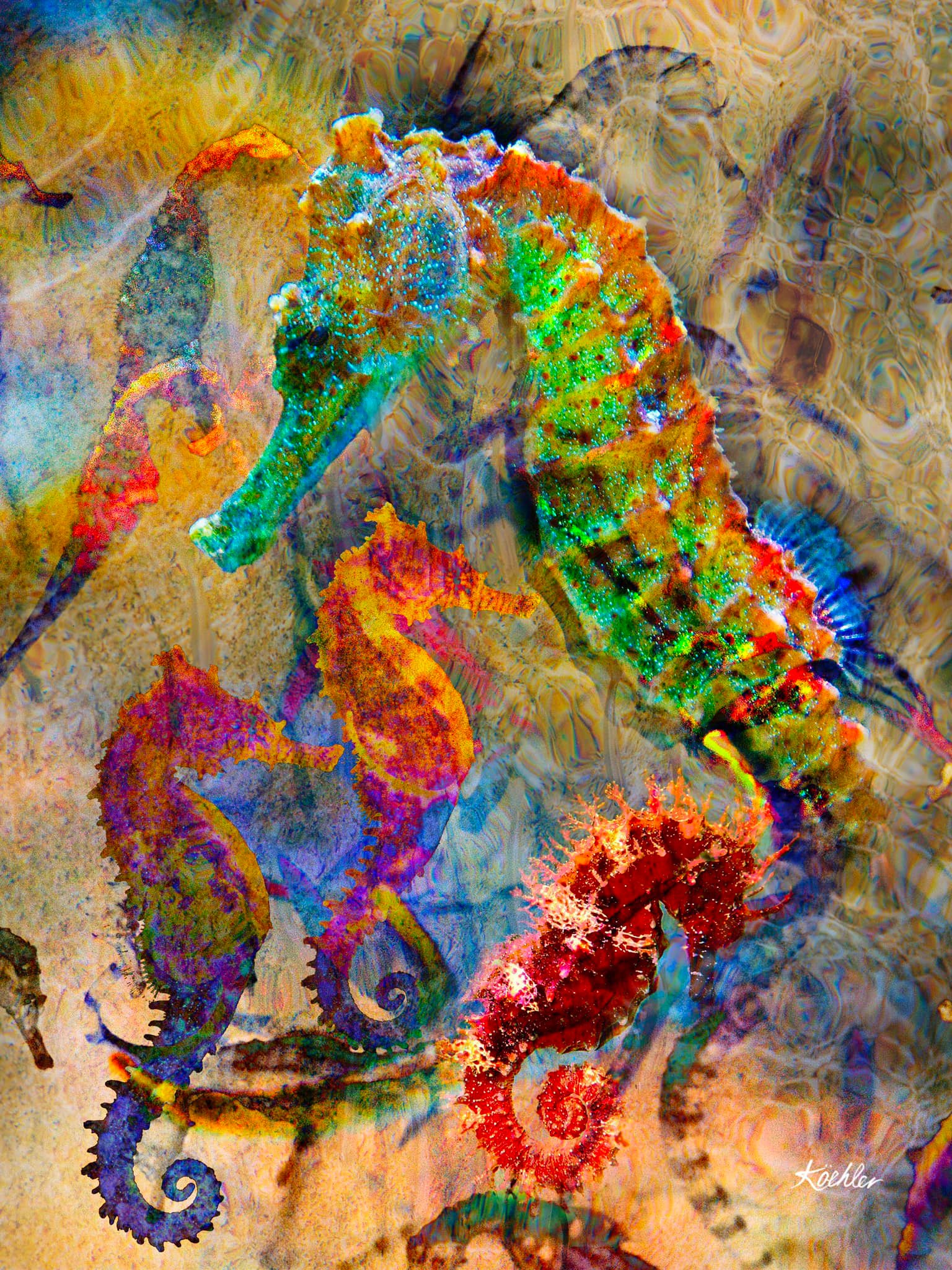

As with Photoshop, layering was a key element with ProCreate. Digital layers are like an old Disney animation, with cells layered on top of each other to get the final effect. The great thing about layers is that they can be removed, altered, or moved up or down. You can also create different effects with each layer by darkening, colorizing, and lightening them, or overlaying any number of effects that can be used or turned off quickly, giving the artist a diverse series of looks for the work.

This breakthrough in equipment and software made it super easy for me to simply create art. No pulling out the drawing pad or setting up an easel. No schlepping out to a beautiful spot, except to take a photo. It was easy, so I did it. It satisfied all my desires for ease of use and speed, and offered me a huge range of options. At first, I was tentative and essentially retouched the photos I took. But over time I began experimenting with bigger brushes to show the marks and become more expressive.

Strong color became my trademark. I experimented with color alterations and shifting colors to create effects. Eventually, it began to work and some of my artist friends called me a colorist. I was cool with that, and I also found out that it is easy to shift from cool and amazing colors to too much color. Easy to over or under do it. Still a learning experience.

As I had done way back in 1994, I began taking photos and doing digital portraits of friends and family who were willing to pose. I would take the chosen photo and remove the background, then paint and retouch, add a background and off I went. I would usually give the person a print or even a framed canvas. Most of the time they liked it, but sometimes they did not, as I could be heavy-handed with my experimentation. All artists want to please others, but sometimes that is not possible, and only the artist is pleased.

I was asked to do some portraits for hire, but priced myself out of the market on purpose, because I did not feel I was ready, and did not want a client telling me to smooth it out, or add red, or why did I make her nose green. The commercial aspect interested me not. Maybe one day, but even then I would insist on doing it my way—or the highway.

I would stare at that person for hours as I worked on their iPad portrait, so it was quite a lovefest while I studied all aspects of their face. That was the primary reason for creating the portraits. It was an act of love and friendship, a personal and very intimate gift that I could give. No different in essence from the Quicktake 100 portraits, just a lot closer.

Dogs have been a key part of my art development, as you will see. Max the dog, and now Boomer, have posed for me countless times as they search the dunes for the elusive dune rats, or simply held still as I told them to SIT!

My grandkids Elijah and Lillian also provided me with countless photos that lent themselves to art projects. Using them as a basis for surrealistic images was a lot of fun, and produced perhaps some of my best work.

Over the past few years, I have caught a little flak from some of my artist friends for not drawing from nature, a.k.a. Plein Air painting. I actually tried it a little, but did not like it. Too slow. So much better to manipulate a photo that I took. After all, that is exactly what photographers do, and no one gives them flak. Ask my friend Glen McClure if he manipulates and does post-production work on his photos. Of course he does digital dodging and burning to lighten or darken, respectively. Begin with nature. Add artist.

So, for me taking the photo was my plein air imagery, upon which I would paint. The photo itself is the realistic rendering upon which I added my layers of imagination to make it my own artistic expression.

My friend, the master artist and author Peter Bragino, says that an accurate rendering of a subject does not make it art, and that art is the expression of the subject by the artist to make it uniquely personal and different than the original rendering of reality. I tend to agree, but the illustrator and photo-retoucher in me might argue the point. A photo is a rendering, and some renderings transcend into art by their beauty and ability to capture the subject as is.

The photo paintings I have done typically take three-to-four hours, sometimes a bit less or more. Very fast compared to some artists, but I never liked the idea of taking days, weeks, or months on a piece of art. Yikes! I subscribe to the Vincent Van Gogh approach of working feverishly fast until exhausted by the work, at which point I would take a break to recover—until the next spell took me and I was off again on my next series. Vincent would often produce two-to-three paintings a day. My norm, with a full-time job, has been one piece a day..

My body of work since late in 2018 is about 250 pieces. I have narrowed those down for this book and for the show of my work to fewer than forty works. Each is shown in one of five categories: dogs, grand kids, self-portraits, Lynnhaven River Series, portraits, and breakthrough.

The breakthrough art is both a revelatory moment of discovery for me, and an apt description of the technique I have found. My work before proved my ability to render and create realism and surrealism from life using representational depictions of life.

The breakthrough moment came when I casually started layering multiple images in such a way as to create something unexpected, an abstraction of life if you will. In other words I did not set out to abstract as a conscious plan, but stumbled into it by daydream wanderings. The words I used on that first piece was “wow!” I continue to use that word quite a lot after creating over 25 pieces in this breakthrough style, because the many options of layering, color shifts and filter options create literally thousands of options to experiment with, an artistic Rubik’s cube of possibilities.

As I state in that section at the end of this book, I do not know if this will be my last style of art I use. But I do know that it opens up an endless world to me, and for that I am most grateful.

And now… the art.